| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| IN common with most other budding road car manufacturers of the nineteen fifties, Jack Turner had a wealth of competition experience upon which to draw. From being a driver of some note, he'd turned to constructing a variety of Turner specials and competition machines, not the least of which was his Grand Prix car of 1953. But his re-investment of experience produced its greatest rewards with series production of a highly capable road/race convertible sports car for the enthusiast.

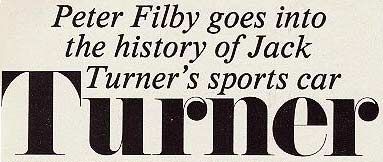

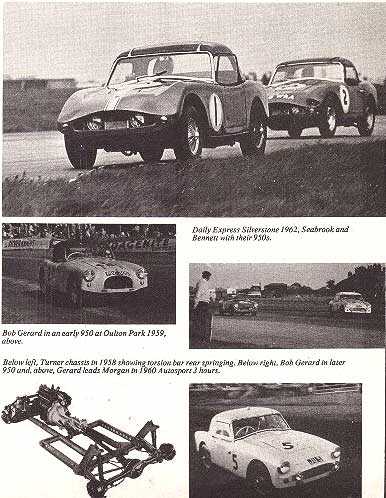

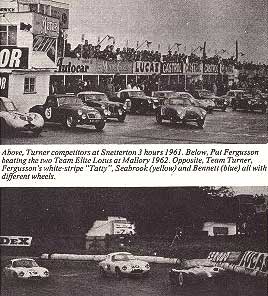

Between 1954 and 1956 a limited number of Austin A30 powered Turner 803s left the Turner workshops on Pendeford Airport, near Wolverhampton. Unobtrusive in appearance but solid in construction, the 803s quickly caught the attention of club racing enthusiasts, for whom their cost and specification were ideal. The combination of a glass fibre body, rigid twin tube ladder frame chassis, independent coil and wishbone front suspension, live rear axle, and turned BMC "A" series engine created a worthy competitor that would happily double as a practical road car. Progressive development resulted in the Turner 950's appearance in 1956, complete with the Austin A35 948cc engine. With twin 1¼ in SU carburettors, this unit produced 43bhp at 5000rpm, not a stunning figure, but a respectable one considering the car's mere 10½cwt. The Turner's real strength, however, was in the way it applied those 43 brake horses to the road so efficiently - through a rear axle located by trailing arms and a Panhard rod, and sprung by twin laminated torsion bars. Jack Turner's proven ability had evolved a thoroughly correct basic design. The first leading lights to emerge amongst the many keen Turner mounted race competitors were John Baldam and Austen Nurse. They brought their Turner 950s home in first and second places in the Autosport Championship of 1958. With the assistance of B. A. Gilbert, whose Turner was placed sixth in the championship, the Turner team also collected the team prize that year. During 1959 the prominent name was that of well known pre-war ERA driver Bob Gerard, who had for some time been a Turner agent in Leicester. His carefully prepared white Turner 950 could regularly be seen on the racetracks throughout the year. Gerard capped a highly enjoyable season by once again giving a Turner the honour of winning the Autosport Championship. R. G. Falconer was close behind in third place with another 950. Waves of Turner success rolled into 1960 ever stronger. The cars of Robin Bryant, Bob Gerard and RAF officer K. W. MacKenzie grabbed the first three places in their class in that year's Autosport Championship. However, they were quite unaware that a small Derby car sales concern was preparing to steal the limelight. Nestling in the gloomy railway arches at Friargate, Derby, Motorway Sales (Derby) Ltd, more specifically its directors Gordon Unsworth and Alan Smith, were selling the secondhand sportscars of the day - Sprites, Elites, Elvas, Astons and so on. Alan Smith, an ex-Reg Parnell mechanic was rapidly building a reputation as an engine turner of note, particularly with Aston Martin and Coventry Climax units. Looking for business expansion, the two men had noticed the Turner's recent race exploits and decided that the recently introduced Turner Climax, with 1098cc FWA engine, could well be a "natural" for them. Early in the summer of 1960, Motorway Sales Ltd became Northern Turner distributors and owners of a pile of components that they felt ought to resemble a Turner Climax when bolted together. Naturally, if that car could be a success in competition, Gordon and Alan knew there would be not better basis upon which to sell the marque. To date the most competitive Turners had been virtually standard cars upon which little development work had been undertaken other than engine tweaking and otherwise very careful assembly. Gordon and Alan decided to take the matter further and produce a thoroughly prepared racer. Its weight having risen to 11¾cwt. The Turner Climax, now designated Mk I,was no longer the light-weight it had been. Within then current regulations the car embarked upon a drastic diet to slim wherever possible. Circular cut-outs appeared in the steel chassis outriggers, the door sills and even in the hefty handbrake lever. Off came the steel inner wing panels and the steel boot floor to be replaced with aluminium, a similar fate being met by the exceptionally heavy glass fibre doors. Even the glass fibre lower body panels and valances received due attention, yet the only obvious exterior change was in the car's nose, where the headlights were repositioned in the grille and the front wings subjected to some aerodynamic development. To reduce turbulence between car and track, a full aluminium undershield was fitted. The diet's end result was a dramatic weight loss of no less than 3cwt - more than 25%! Engine preparation was Alan Smith's department. Meticulous engineering (including reworking the head to Alan's own design), blueprinting and balancing saw the FWA unit, with twin DCOE Webers, producing power to its full capability. In standard form the A35 derived front suspension and homegrown rear suspension would take any Turner through a slow corner considerably faster than similar machines. On fast, gently curves the car was less happy, refusing to slide around and tending more to hop around. But time dictated. Knowing that their Turner would never match the all conquering Lotus Elite's ability to take 120mph bends flat out, Gordon and Alan resolved only to lower its suspension and put in further development as time presented itself. They knew only too well that most British circuits were tight and twisty - ideal for the Turner.  Somewhere around the middle of July 1960, this most meticulously planned Turner Climax racer was taking shape carefully, if more than hurriedly. Madly might be the word, for its first race was to beat Mallory Park on the 31st of that month in the hands of Pat Fergusson, a local Derby man who'd had plenty of experience with a similar car, the Elva Courier. Having led a hand to mouth financial existence to prepare the car, Gordon and Alan prayed for success. Yet although the FWA engine had been bench tested, there had been no time to test the complete car. In particular at Mallory that day, it ran for the first time, its unpainted glass fibre a milky opaque surface, looking very strange in the sunlight. Despite the effort involved in its preparation, Pat Fergusson's steed did not look a pretty sight as it sat high on its unsettled suspension and well back on the grid for the race that day. Things hadn't gone too well in practice. Yet, once the race was under way, the Turner's erratic and entertaining handling failed to slow its progress through the field much to the spectator's delight. The race commentator was rather startled too, "Just look at that Turner," he said excitedly, "it may look tatty, but just see how it's going!" Of course the tag stuck well and truly. After a highly creditable third place in its first race, there on the grid at Snetterton in August sat the same Turner, painted now, with the legend "Tatty Turner" proudly borne on its front wings! And this time Tatty won outright . . . and repeated the process in the up to 1500cc sports car event at Mallory Park in September. The last race of a restricted season was at Snetterton in October where Tatty gained second place among the up to 1600cc GT cars. Only four outings had been made, but they'd been made in fine fashion. During the winter that year, Tatty Turner needed negligible overhauling. Various suspension settings had been tried, all to little avail - the car still felt unhappy on fast bends. Small mercies were due in that the suspension had at least settled down, gradually improving handling as it did so. The car's optional 9-inch front disc brakes required more effective cooling, while the only other modification was the fitting of a ZF limited slip differential. However, Gordon Unsworth now saw the need for some sponsorship to assist Motorway Sales (Derby) Ltd through the planned full season for 1961. His first approach to Jack Turner was met with indifference from the practical man, an engineer not taken to writing letter and dealing with paperwork. Nor was he interested in handing out any financial sponsorship, but he did supply a stack of letter headings for Gordon's use. Thus contracts were eventually signed and the newly formed Team Turner could at least look forward to free oil, free plugs, cheap tyres, easier race entries and cash payments from the bonus schedules of large companies such as Esso, Champion, and Dunlop. Pat Fergusson was to remain Team Turner's senior driver, in charge of Tatty. Despite the car's lack of handling refinement, he had enjoyed himself immensely in his first four outings. In any case, he'd been used to strange handling quirks with his Elva. Rumour had it that the Elva's founder, Frank Nichols, used to say, "I always set my cars up for neutral handling - no understeer, no oversteer," while Elva drivers used to say, "neutral handling in an Elva means straight on!" But Fergusson liked to have a wrestle with his car. A competent rather than a brilliant driver, the real strength of this quiet, gently man appeared when he was behind the wheel. A real individualist like many good driver, he possessed a wicked sense of humour and great reserves of courage. He'd needed the latter more than once whilst trying to escape from Colditz camp, where he was held prisoner during World War II. He'd been one of the resourceful group building a glider in the prison attic with the intention of launching it down the sloping roof for a flight to freedom, shortly before the war's end. By the time Team Turner's second driver, Brian Bennett had been enlisted in July 1961, Pat Fergusson had already given Tatty four firsts, four seconds, one third two fourths and only one mechanical failure in twelve outings. In addition, though wildly out of class in two pre-season 2000cc warm ups, he had nevertheless managed seventh and third placings. Undoubtedly, Tatty Turner was already the best known racing Turner and the car everyone wanted to beat. Prior to his involvement with Team Turner, Brian Bennett had tasted mild success with a racing Sprite. Now he was keen to emulate Tatty's success, so Motorway Sales Ltd supplied him with a BMC 948cc engined Turner kit. To bring the car into line with Tatty, the company assisted Bennett with the build, carrying out mostly the same modifications as on the earlier car. Alan Smith once again produced an immaculately prepared engine with reworked head, special camshaft, and twin 1½in SUs, all balanced for efficiency. The two team cars, both painted BRG were now distinguished by their longitudinal stripes - Tatty with a white one, Bennett's car with a blue one. Due to their different engine capacities, the two cars were rarely in the same race and not always together at the same circuit. But as "Teamo" - team manager, organiser, and dogsbody - Gordon Unsworth worked out how best to cope with regulations and where the team stood it best chance of gaining results. Whilst Gordon handled all entries and looked after Tatty, Bennett maintained and transported his own car. Feeling confident of their car/driver combinations, Team Turner's approach was one of professionalism allied to meticulous preparation. The cars were always trailered to circuits and Gordon was quite adamant about repairs, If we thought we'd have to strip something down in the paddock grass, we wouldn't have gone to the race!" Finances remained under regular review, of course. Large, and often small, hotel bills were out of the question. It was more often a very early morning start when Tatty was racing at one of the more distant circuits. The greatest reward for such effort was heady success. Whilst Brian Bennett did well, Pat Fergusson and Tatty did exceptionally well. From 27 starts in 1961 Tatty grabbed no less than 23 placings, including fourteen firsts, six seconds and three thirds. Many of these places were in up to 2000cc capacity races. Another notable result was a fourth overall in a Formula Libre race where Tatty had been pitched in amongst 3-litre single seater Formula cars. But the climax to the season came when Pat Fergusson brought Tatty in third overall in the Autosport 3-hours at Snetterton late in September, in the process of winning the Autosport Championship series for up to 1300cc cars.  Such a fine performance did not totally overshadow the efforts of Brian Bennett and Team Turner's third member, John Seabrook, who had joined late that season. Adorned with a yellow stripe, Seabrook's car was otherwise almost identical to Bennett's. Another successful Turner that year was Wing Commander K. MacKenzie's special bodied Alexander Turner, a car often amongst the results and lap records. Alexander Engineering of Haddenham, Bucks were Jack Turner's southern agents. Rather than sell standard cars, they fitted their own aluminium crossflow cylinder heads to the 948cc engines and sold cars as Alexander Turners.

Throughout 1961 Tatty had competed in a variety of guises. In open form with a small aero screen and half tonneau cover, she had been eligible for sports racing events. Often for GT regulations she would have to tun with a standard screen and glass fibre hardtop, but would also occasionally squeeze through with a short, wrap-round perspex screen and rather a makeshift hood. To comply with regulations, this hood could be erected with a struggle, and had occasionally stayed put for a whole lap when required to do so. Thankfully, officialdom had never demanded more than one lap under full weather equipment - it was very doubtful whether Tatty's hood would have stayed up longer anyway! The only change for Team Turner's 1962 season was Tatty's new 1216cc Climax FWE nestling in the engine bay along with the ZF gearbox. Approximately 108bhp was now on tap, but the new unit preferred lower rev limits than the 8500rpm of the old FWA. Jack Turner's hearty approval of Team Turner's 1961 exploits had not changed his attitude one financial iota. So it was under Gordon Unsworth's untiring organisation and strict financial control that Pat Fergusson, Brian Bennett and John Seabrook once again went into battle. Tragically, the team was reduced to two cars early that season when Bennett died in a road accident. However, Fergusson soon restored team spirits. With his customary confidence in the car and himself, he set out, as always, not only to beat the Lotus Elites, but also to grab every opportunity of showing a clean tail to any piece of machinery that might be bigger or faster than Tatty. Including one incredible run of six consecutive firsts in June and July that year, Tatty's record for 1962 was eleven placings from fifteen starts. For the second year running, the now famous Turner gained third overall in the Autosport 3-hours at Snetterton whilst winning the 1300cc class in the series as a whole. But perhaps the happiest moment of the year was at Mallory Park late in the season. In a race against a field of no less than twenty-one Elites, who after all had by then acquitted themselves very well at Le Mans, Fergusson took Tatty away from pole and never heard a murmur from any one of Colin Chapman's monocoque beauties. It was one of Tatty's most memorable victories. In two remarkable seasons, Tatty and Team Turner had more than proved their worth. Motorway Sales had benefited greatly. So too had Jack Turner with over 250 cars produced in the financial year ending 30 June 1962. In the lighthearted atmosphere of club racing, enthusiasts everywhere were gaining great pleasure from the little Wolverhampton made sports cars. But the achievement of an object had its inevitable result. Overburdened with work, and still regretting the lack of financial co-operations from Jack Turner, Gordon Unsworth decided to split up Team Turner. The project's success had given great satisfaction. Perhaps the spirit of those seasons is best summed up by Gordon, Like most of our good humoured competitors, we did terrible things in those days. Tatty had a dashboard switch to turn the brake lights off. With something bigger right up his backside after being caught on a straight, Pat would go three or four times into corners with his brake lights working normally. Naturally the chap behind would see them and brake himself. But then Pat would flick the switch. On the next corner, the bigger machine's driver would be waiting to see some brake lights, brake far too late when he realised what was happening, and generally get in a hug tangle while Pat cruised off into the distance!" Warwick Banks became Tatty's new owner. Over the 1962/3 winter Alan Smith had fitted another power unit, basically a 1098cc Climax FWA, reworked to take advantage of the new 1150 category. Using some German Mahle pistons and liners, 1098cc became 1147cc, now producing approximately 97bhp. While Banks raced the car in otherwise unchanged form, Gordon Unsworth agreed to continue entering Tatty under the Team Turner banner for one more year. And what a year it was . . . A very accomplished driver, Warwick Banks handled Tatty in an altogether smoother and less dramatic fashion than Pat Fergusson had done. The secret of his success lay in his skilled control of power and his results speak for themselves - Thirteen firsts, two seconds, three thirds, and only three failures to finish from twenty one starts in 1963. One additional and exceptional outing was at the Goodwood Whit Monday meeting. There was the still rather ordinary looking, still Tatty Turner crossing the line fifth overall behind the glamorous might of Mike Parkes' Ferrari, two other Ferraris, and Graham Warner's Lotus Elan, a full 25 seconds ahead of everybody else. In a later letter to the Turner Sports Car Club, Banks summed up his views on Tatty, First time out the car gave me the feeling of being a winner - very taut, compact, and very controllable. The engine was magnificent and only required oil and big-end bolt changes as total maintenance throughout the season. Team Turner's last surviving representative was not alone amongst the results in 1963. Riding a 1650cc (bored out 1500cc Cortina) Ford powered Turner, John E. Miles was also remarkably successful. In the second half of the 1963 season and the whole of 1964's, Miles scored no less than fifteen class and overall wins from seventeen outings. In the two other races his car broke down whilst in the lead! Mile's car was mechanically similar to its Climax and BMC powered sisters except in its use of Triumph Herald coilspring and wishbone front suspension - standard specification for the Ford-powered Turner that had appeared from 1961 onwards. Miles' most notable achievement was in winning the 1964 Veedol Sports Car Championship. As the sixties advanced, the Turner's domination of GT and production sports car racing diminished. The Diva/Marcos/Ginetta/Lotus Elan era had arrived. Team Turner was finally dissolved after the 1963 season, taking with it a great satisfaction from having been so successful and having provided so much pleasure. The team's highly enthusiastic following had witnessed superb races, exceptional results, and the securing of many lap record, some of which will never be broken. Though his company went into liquidation early in 1966, Jack Turner's cars had earned great respect. Indeed, many are still racing today, though will never recapture those many delightful moments between 1958 and 1964 when they outsmarted and dominated the much heavier metal. Certainly, Turners were true giant killer of their day.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||