| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

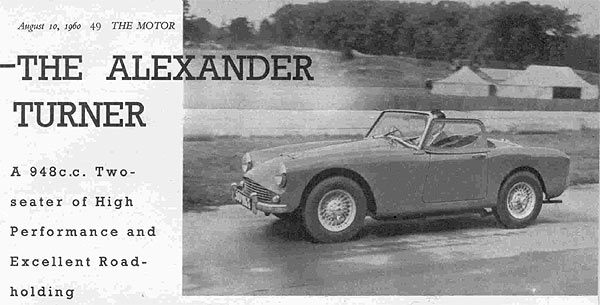

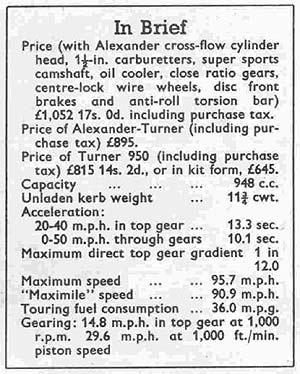

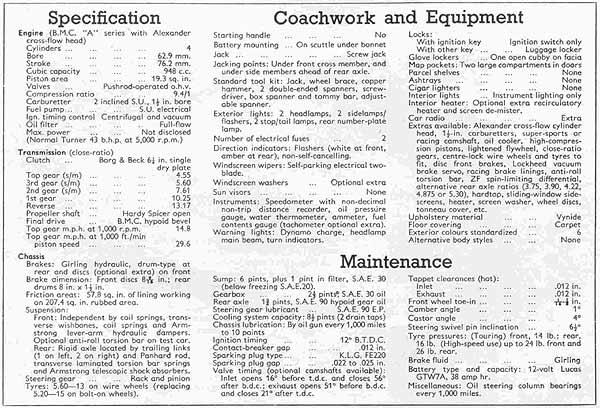

| BUILT at Wolverhampton in modest numbers, the Turner is a small sports car carrying full road equipment which, costing rather more than some other two-seaters of similar engine size, has won a great many races because it combines low weight with tenacious roadholding. From the factory, it is offered with a tuned 948 c.c. Austin or a 1,097 c.c. Coventry Climax engine; our test model, loaned by Alexander Autos and Marine Ltd. (Turner distributors for S.E. England), was their own special version of the 948 c.c. model, using a light allow "cross flow" cylinder head. Other extra-performance equipment on our test model included S.U. carburetters of 1½-in. bore, a super-sports camshaft, close-ratio gears, disc front brakes, centre-lock wire wheels shod with 5.60-13 Dunlop Nylon tyres, an anti-roll torsion bar, and an oil cooler; also there were such refinements as a heater and windscreen washers. With all these extras aimed at making it a very fast 1-litre competition car, the Turner remained an extremely pleasant open two-seater for ordinary use in weekday or weekend traffic.

Beneath its glass fibre and plastic body, the Turner has a straightforward twin-tube chassis. Apart from a tuned Austin A35 engine, it uses an I.F.S. assembly from the same source, rack and pinion steering, and an Austin A35 rear axle kept very precisely under control by two radius arms, two laminated torsion bar springs, one torque reaction link and a Panhard rod. There is nothing revolutionary about the chassis, but its details have been carefully worked out to provide an exceptionally high standard of roadholding. A reasonable degree of sport-car firmness in the springing does not prevent the Turner riding quite comfortably when its tyres are at ordinary touring pressures, even across the rough grass fields which serve for car parks at motor racing circuits. With the extra front anti-roll bar, which was on the test model, it corners fast with even less roll than most other sports two-seaters, wheel adhesion and full controllability being retained up to remarkably high cornering speeds.

Around town, some frictional damping in the rack and pinion mechanism gives the steering a slightly dead feel, but above 30 m.p.h. or so this unwelcome stiffness is lost. A driver soon acquires confidence that the Turner will go just where he wishes, on the straight or around corners, with a minimum of conscious steering. In the 70-80 m.p.h. speed range a good deal of scuttle shake was evident, but this shake seemed to be at least in part a shortcoming of the coachwork (perhaps it is unwise to mount a heavy 12-volt battery quite high upon the scuttle of a non-metallic body) and was not accompanied by any loss of steering precision.  Disc front brakes are an optional extra for Turner cars with the 948 c.c. engine, and they worked with smooth, silent effectiveness. Usually high pedal pressures were needed on our test model, but we understand that on current production models the pendant pedals have been replaced with their leverages altered to reduce the effort required from the driver; also that despite the expectation that this change would be accompanied by longer pedal travel, an extra inch of legroom has in fact been made available in the cockpit. This body does not look strikingly low, because it extends up to shoulder level beside and immediately behind the driver, who is better protected from back-draught than in many other open cars. None of the luggage accommodation is inside the cockpit; two huge door-compartments and a cubby hole providing ample stowage for almost anything likely to be "wanted on voyage." Under lock and key protection, a very considerable quantity of luggage can be carried in the rear locker, which has the spare wheel flat on it floor. Rather inconveniently, the small 6-gallon petrol tank also has its filler inside the luggage locker.

Weather protection is well looked after in the conventional modern sports car manner, by rigid-frame sidescreens, which are very easily installed or removed, and by a hood incorporating three big flexible windows which has a loose fabric and a removable two-piece frame. Sidescreens incorporating sliding window panels, and a removable hard-top, are available if required. Adjustment of the two bucket seats is confined to alternative bolt-down mountings, and for tall people legroom at first seems rather limited, especially as intrusion of the gearbox enclosure into the cockpit leaves no obvious left foot position comfortably away from closely-spaced pedals. After a while, however, a driver seems to settle down behind the offset-to-the-left steering wheel and makes quite long runs without complaining of any discomfort. Carrying the optional tachometer on the test model, the facia with its individual instruments on a panel covered in black plastic fabric seemed entirely appropriate to a sporting car, there being a thermometer, oil pressure gauge and ammeter as well as the fuel contents gauge and speedometer. The two doors do not extend far enough forward to make exit from the body really easy.

In rather cool summer weather, the engine always started easily without needing any help from the choke and was almost completely devoid of any warming-up temperament. Running without a fan (although there is room to fit one), the test engine would warm up the water from its usual 60° C. to about 70° C. if worked hard, or to 85° C. in London traffic, and lost some water at high r.p.m., but would seem unlikely to overheat in any but very rare conditions. Despite a compression ratio of 9.4/1, the 96-octane grades of Premium petrol seemed acceptable and the use of 100-octane fuel a luxury.

In its Alexander form, the Austin engine has a light-alloy cylinder head, with four semi-downdraught inlet ports on the right and three exhaust ports on the left. Our test car had 1½-inch S.U. carburetters on long pipes instead of the 1¼-inch bore carburetters usually fitted, and had the optional super-sports camshaft. Mechanical clatter was prominent at low speeds and the engine roared healthily when working at the very high r.p.m. of which it is capable in this tuned form (we are told that at 7,000 r.p.m. the power curve still points upwards), but whilst the high general level of noise was rather tiring when all the weather-proofing was in place, it became less so with even one sidescreen removed, and cockpit noise is not objectionable when the hood is folded. Less highly turned versions of the engine would obviously be quieter, although the bodywork does not carry any apparent sound-deadening material. Silencing of the exhaust is sufficient to let the available power be used without much restraint. Due apparently to a resonance effect in the special long inlet pipes at around 3,000 r.p.m.use of full throttle produced blow-back from the carburetter intakes which could be smelt inside the car, and which, despite some "nursing" of the throttle during our performance tests, is reflected as a flat-spot in the top gear acceleration time from 40 to 60 m.p.h. Beyond this critical speed, the engine really starts working, and the special, very close ratios in the gearbox of our test car made it easy to keep always above 3,000 r.p.m., even if 5,000 r.p.m. was never exceeded. The unsynchronized and rather noisy 1st gear would greatly improve the getaway from rest, but despite the handicap of a 10.25/1 starting gear, such acceleration times as rest to 60 m.p.h. in 13.6 secs., rest to 80 m.p.h. in 26.5 secs., and 19.7 sec. for a standing-start ¼-mile indicate the remarkably vivid performance of which this fully equipped 1-liter car is capable, even when carrying two men and a moderate weight of test equipment. With hood and sidescreens erect, a mean timed speed of more than 95 m.p.h. was recorded, and with a tonneau cover over the passenger seat even higher speeds were attainable without over-reving the engine. Whilst the 3,000 r.p.m. flat spot past which the engine preferred to be "nursed" of half throttle was a decided nuisance in brisk, as distinct from fast, driving, the engine had quite a dual personality. Around town, the Turner in its tuned form would potter along without 2,500 r.p.m. ever being exceeded, running smoothly enough and never threatening to foul its sparking plugs. Allowed to rev. fast, the engine showed the other side of its character, and even if 6,000 r.p.m. is thought preferable to 7,000 r.p.m. as an "everyday" limit, the indirect gears provide speeds of 39 m.p.h., 53 m.p.h., and 72 m.p.h., which permit very rapid overtaking of main road traffic. When true cruising speeds of 85-90 m.p.h. were sustained along the Motorway, the indicated oil pressure fell very gradually from 50 lb. to 35 lb., but always recovered as soon as speed was reduced on regaining old-fashioned roads. On the really steep hills which can be encountered in some parts of Britain, certain features of the highly-tuned test car which would be very advantageous on a racing circuit became a disadvantage. The special close ratios (with which 1st gear is actually higher than the normal 2nd gear), together with the super-sports camshaft and oversize carburetters which did not improve the torque at low r.p.m., made re-starting on steep hills tricky, and experiments on 1 in 4 heated up the clutch (normally very firm indeed in its action) to the point at which slip set in temporarily. Finish of the moulded bodywork is good enough for the use of metal doors to be not visually apparent. It would seem that an owner might need to go round some items such as boot lid hinges with a spanner occasionally, but the bodywork has quite a professional air about it, and a good instruction manual illustrated with drawings and a wiring diagram is provided with each car. Some details which we disliked, such as a horn control mounted on the facia where it hardly seemed as accessibly as might be wished, could soon be changed by and individual buyer to meet his own tastes. For the majority of sports car buyers, the Alexander-Turner as it was submitted to us for test would be rather too highly turned. Dispensing with the oversize carburetters or the super sports camshaft, and perhaps also with the close-ration gears, would save money and presumably make the car quieter and more flexible for everyday road use, probably without dropping the maximum speed below about 90 m.p.h. But even some rather elusive fuel starvation trouble which occurred during hard acceleration or at high r.p.m. (and which took a long time to track down as resulting from an invisible perforation in a plastic pipe which was letting air into the suction side of the fuel pump) did not damp our enjoyment of a comfortable, lively and exceptionally controllable little car.  |