| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

| KIT CARS have grown up: they can still look awkwardly angular, giving away their pre-war, tomboyish beginnings, but they can also be sleek and sexy.

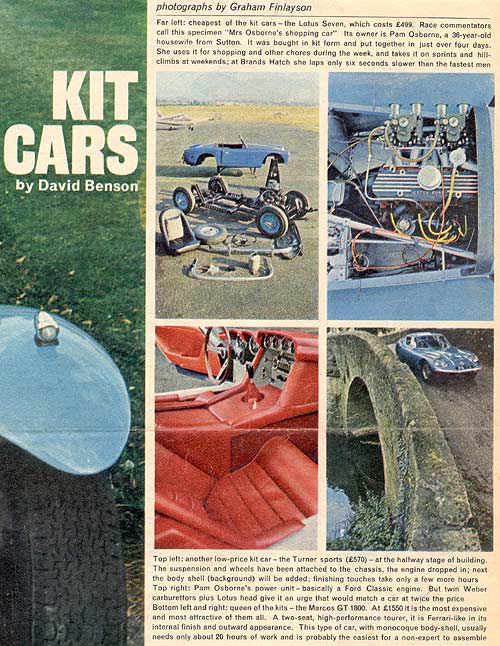

In the 1930s there were three-wheelers and four-wheelers, built from kits by enthusiasts with little money, plenty of time and a longing for a car of their own. It was an age of save-money-and-do-it-yourself. If you wanted to go flying you built yourself a 'Flying Flea', put in a motor-cycle engine, and took off from the nearest field. If you wanted to motor, you bought a kit or a magazine called Practical Mechanics edited by the father of do-it-yourself, F.J. Camm. He once ran a six-month series of articles on how to build a three-wheeler with a wooden chassis. You started out with a couple of stout bits of timber, a complete workshop -- and time . . . It could take up to two years of spare time to build. The modern kit car is entirely different. All you need is practical application, a few hand tools and a couple of free weekends. A London solicitor, who wanted a sporting Grand Touring car, bought a Marcos GT 1800 in kit form. He had never before assembled anything more complicated than a Meccano set. He had the usual hand tools found in any garage: a set of spanners, two screwdrivers (one a Philips type), a couple of hammers, metal files and a set of box spanners. The parts were delivered in boxes on Friday morning and he spent the evening unpacking and laying them neatly around the main body shell. This shell is made of wood and fibreglass and is the core of the whole car. On Saturday he first assembled the front and rear suspension units, attached them to the body, then bolted on the wheels. Now he could move the car about. The next job was the most difficult and required the help of a friend and one piece of specialist equipment - a hoist - to lower the engine and gearbox into position. This, plus the connecting-up of the transmission, took the rest of the day to complete. At one point he discovered that the had mislaid the propshaft bolts and telephoned the factory. They promptly had a set put on a passenger train to his local station. Sunday was devoted to wiring up the car and bleeding the brakes to get rid of the air locks in the brake fluid. This was another job that required an assistant, this time to push the brake pedal while the valve on each brake drum was adjusted. Late on Sunday afternoon the solicitor telephoned a directory of the Marcos company at his home to check on the wiring of the overdrive. The director, Gem Marsh, recalls: "I referred him to the page in the workshop manual that deals with wiring. Under the Customs and Excise Act I am not allowed to five him specific instructions or any help during the building of the car." The Customs and Excise are very sensitive about kit cars and have imposed somewhat stringent regulations governing the sale and assembly of kits. The is not surprising as, if you buy a car in kit form, you pay no purchase tax. In the case of the Marcos this amounts to a saving of £304. Apart from the fact that the kit builder must not obtain professional assistance, the car cannot be assembled on the premises of a commercial garage. Neither can the manufacturer supply any assembly instructions. Most people who buy kits get around this problem by buying a workshop manual. They look up the instructions for dismantling - and work backwards. Manufacturers also help by offering a free 500-mile service at the works and by insisting that the new guarantee is not valid until the car has been checked at the factory. Gem Marsh says: "The Marcos is the most expensive kit car on sale. It is probably the easiest to assembly, but we want to make sure it is also the safest: after all, it does 120 m.p.h." Kit cars have advanced in other ways. They are now acceptable to hire purchase and insurance companies. A few years ago there was a boom in the fibreglass body shell business. Thousands of enthusiasts bought these delectably shaped shells and dropped them straight on to elderly engines and chassis from Austin Sevens, Fords and the like. They looked perfect, but under the skin they were often clapped-out - and dangerous. As a result, kit cars got a bad name as a class. They were impossible to insure and difficult to sell without considerable financial loss. Most customers for the Marcos kit car come from the professional classes - doctors, dentists, stockbrokers and solicitors. They buy and build them because they want to own a highly individual car of the type they could not otherwise afford. One of them, a London dentist, put it: "You not only save money, have something quite unique in the neighborhood, but you also get a tremendous satisfaction out of having created the thing yourself." None of the kit cars is notoriously expensive; all are in the £500-£1500 range. Though they are, as a species, for the enthusiast, many make excellent cars for general use. And if you like the look of one, but don't want the chore of putting it together, any of them can be bought, on order, off the peg - with, of course, the purchase tax added.

|