| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

| Turner versus 'Frogeye': the Turner, with glass-fibre body, is easier to restore, but lacks Sprite's charming looks |

|

|

The Austin Motor Company has often produced mass-market sports cars, and usually they were developed from current family models. This trend is exemplified by the Austin Seven, with its range of sporty models such as the Ulster and Nippy. It also inspired several coachwork concerns, particularly SS cars and after the war, a deluge of glass-fibre bodyshells and specialist kit cars to supply the ever increasing market for affordable sporty motoring. The production of MGs from the lightweight juniors, M and J types (also derived from a family model, the Morris Minor), to the TF and MGA saw a continual increase in engine size up to the 1500cc class, and price tags over the £1000. All this left a gap in the market for the 'Midget' sports car. The 'Tiddler' Sir Leonard Lord, who became Chairman at Longbridge after the death of Austin, had already proved the success of the company's association with Donald Healey with the Austin Healey 100. Lord and Healey clearly realised the potential of a smaller sister for the 100 model, and in the winter of 1956 the concept of the 'Tiddler' - as the prototypes, Q1 and Q2, were affectionately known - was born. Gerry Coker, previously responsible for the graceful curves of the 100, styled the prototypes, which incorporated novel pop-up headlights (Coker left the company for America in 1957). Healey's genius for instinctive engineering and marketing led the development. Unitary construction - a first in the English sports car market - with the boot-less body style and minimal chrome work, as well as maximum use of BMC mechanicals, kept production costs and the eventual price low. With Geoffrey Healey as Development Engineer and Barry Bilbie as Chassis Designer, the final design suited the brief perfectly. Power was from the 948cc derivative of the A-series engine which first saw service in 1951 in the A30. With a three-bearing crank running on thin wall bearings (the first production engine to do so) and a highly efficient cylinder head designed by Harry Weslake, the engine had great reserves on strength for tuning. The crankshaft, valve springs, connecting rods and bearings were all greatly improved, while twin 1 1/8ins SU carbs raised the power to 43bph at 5200rpm. The A35 gearbox was retained, along with the standard 4.22:1 axle ratio. Morris Minor drum brakes were operated hydraulically through a single reservoir, with twin cylinder clutch and brake master cylinders by Lockheed. Front suspension again used A35 components, with single, pressed steel lower wishbones, coil springs, and upper links formed by the Armstrong shock absorber lever arms.

Most significant among the running gear changes was the rear suspension. Amazingly for a low cost car, rear loadings were fed forwards into the rear floor area through quarter-elliptic springs in the style of Jaguar. Axle location was via two trailing arms, and steering by Morris Minor rack and pinion. The unitary chassis was a masterpiece of simplicity and lightness. It consisted basically of a central passenger cell with extensions forward to carry the suspension substructure, and a shallow rear bulkhead cum axle cover. Torsional and beam stiffness came from the deep transmission tunnel, boxed side members and one piece rear skin. There was no opening boot. Thanks to a cavernous, one-piece, rear-hinged bonnet, engine and front suspension accessibility was excellent. The retracting headlights of the prototype had to be dropped partly due to cost, and partly due to the complexity of design required in conjunction with the one piece bonnet. Les Ireland took over from Coker as Body Engineer, his only major change being the fitting of hidden internal door hinges. With its simple pod inset headlights for eyes and cheeky smiling mouth type grille, the Sprite received a rapturous reception from the press. John Bolster, accompanied by Grand Prix driver Roy Salvadori, was very impressed at the wheel around Silverstone, and Bolster predicted an overwhelming demand for the 'Frogeye'. He was right, as a total of 38,999 Mk I Sprites were manufactured before production came to an end in May 1961. The Turner 950, with its production total of 150 cars, may not be considered a threat in retrospect, yet with its extensive competition pedigree and more sophisticated body specification (it as least had an opening and lockable boot) it did on paper offer opposition to Austin. Its creator was John Turner, a race driver of some note with a wealth of competition experience throughout the fifties. His early cars included a highly modified MG K3, and a variety of Turner specials including a Grand Prix car of his own design in 1953. By 1954 he had set up a small production line in his workshops on Pendeford Airport near Wolverhampton, and the car, known as the 803 in accordance with its A30 engine capacity, soon caught on with racing fans. Between 1954-6, 75 cars were built. The car was built around a strong twin-tube ladder frame chassis to which a light glass-fibre body was secured. The bulkhead as floor pan were of steel for extra strength and rigidity, while independent coil and wishbone front suspension and a live rear axle with torsion bars and radius arms produced superb handling. The car's tuned BMC A-series engine producing 30bph and its lightness meant that it was both potentially competitive as a track racer and practical for road use. A top speed of 80mph and 45mpg even tempted pop star Petula Clark!

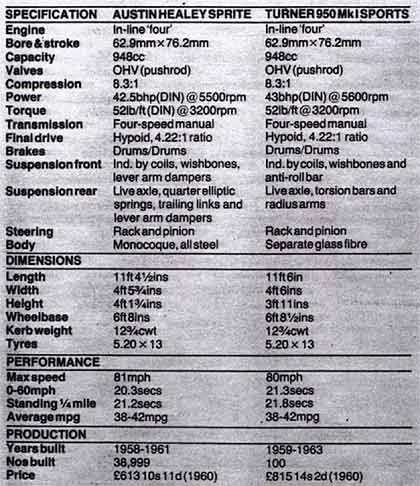

The introduction of the 950 in line with increased capacity of the A35 engine, as usual available in various states of tune to the customer's request, came in 1956. Styling remained much the same with its distinctive fins and egg-crate type grille, while hydraulics replaced the previous hydromechanical brakes of the 803 model. Torsion bars were now laminated, and a Panhard Rod helped the live rear axle handling. Like all Turners, the model was available in both kit form and fully assembled and a high percentage of the 170 production was exported to the USA and South Africa. Track successes John Baldam and Austen Nurse were the first competitors to exploit the Turner 950's track potential, and eventually finished first and second in the Autosport Production Sports Car Championship, and also collected the team prize with the assistance of sixth-placed B.A. Gilbert. In 1959, Bob Gerard, well known ERA exponent and for some time Turner agent in Leicester, took to the track with his carefully prepared white 950. The Autosport series limited modifications, but Mr Bob had new manifolds, careful cylinder head mods (retaining standard valves), twin SUs, and close ratio gears in the BMC box. An anti-roll bar was fitted, the screen raked and the disc wheels perforated to improve brake cooling. The car was incredibly successful, and Mr Bob ended the season as overall Autosport champion, and pride of place at the Racing Car Show in 1960. The Turner Mk I Sports also appeared in 1959 and, although the chassis and suspension was little changed, the bodyshell was significantly restyled with an altogether more modern appearance anticipating the later "Spridget" family. A lower, wider mesh grille and lower headlights revitalised the nose, while the surgery to the fins rounded off the rear wings. Overall,the complete package, particularly with wire wheels, looked very attractive. With the optional overhead camshaft Coventry Climax engine producing 75bph, maximum speed was just over 100mph. However, even the basic package in 1960 cost £1099 compared to £657 for the Sprite. How did they differ in use ? The demon red 'Frogeye' in our midget match belongs to Gary Edwards, a freelance motor mechanic. He has owned the car for a mere eight months, having acquired it from a local garage for £600. Gary had desired a Sprite since childhood, claiming that the car's cheeky looks endeared him to the type. His car is by no means concours, or for that matter totally original, but he uses it every day, and is continually surprised by how much equipment can be stowed behind the seats. His car has recently had a completely new chassis and floorpan. A glass-fibre bonnet was fitted before he acquired it - though not original, it is very much more practical. His Sprite also has larger 165 tyres, which greatly helps the roadholding, and he has fitted 1 3/4inch SUs. For all the car's impracticality for his job, he has few misgivings about his bargain purchase, though the primitive sliding side-screens make an awful din when they rattle at speed. In particular, it is the handling that gives him the greatest pleasure, and with the bigger tyres he has eliminated the chassis' twitchy behaviour. Tolerant wife Terry Filby's fascination for the Turner marque began when he witnessed one such model attempt to demolish a telegraph pole at the Weston speed trials. However, the model's continued success at various race and sprint meetings he attended - including Goodwood, where a Turner still holds the official class record - convinced him he should buy one. This, in fact, is the second Turner he has owned. It was found derelict in a garden, and eventually purchased for £50 in 1975. The lengthy restoration was finished two years ago, and the project could not have been more suitable for his semi-detached environment, though you need a pretty tolerant wife to live with a glass-fibre body on your front lawn for several years. The simplicity of the Mk I Sports was very attractive. The sheet steel body subframe and moulded glass-fibre shell can be easily released from the massive tubular chassis by unbolting the 12 securing bolts, and the lightness of the design was a real bonus during this one man rebuild. The body was in good condition, although it needed a double-coating relamination after roughing down, which helped prevent crazing of the new brilliant yellow paint job direct from a Citroen paint catalogue. Parts presented no problem once their origination was discovered. The door handles are Standard 10, the front bumper A35, while the mesh for the grille came from an A55 truck. Terry has the Alexander modification for disc brakes at the front, and has fitted a single 1 1/2in SU, which, matched to tuned inlet and outlet mainfolds, has much improved the power range. The car also has the Alexander wire wheel option, and Terry has modified the steering arms and lowered the rack to reduce bump steer. The hood design of both cars is identical, although the Turner requires an extra 2ins to the back cover. Both have split hood frames, though the Turner side screens are one-piece compared to the sliding pattern of the 'Frogeye'. Though originally a substitute for an MGA, Terry does not regret his efforts with the Turner, and is at present restoring a second car for hillclimb and sprint work. Besides the car's fantastic handling and inherent reliability, it is his involvement with the club that has given him the greatest pleasure. He has met many new friends - "that's enough to endear you to any marque". Climbing down into the 'Frogeye', it is immediately apparent that the absolute essentials are provided. The dashboard is very sparse, with large speedo and rev counter dominating the view through the two-spoke wheel. In fact, even the rev counter was optional. The passenger side has no glovebox, and the grab handle was an extra. The doors are unlined, giving extra elbow room, while the lower half accommodates capacious pockets. Once the doors are closed, the cockpit is snug rather than tight fitting. Almost immediately you are on the road, the 'Frogeye's' charm becomes clear. Every operation is instant. The rack and pinion steering is direct, and only the slightest movement is required for cornering. The gearbox has the electric switch character with a snappy, short throw close to hand, although even during my short drive it became apparent that the gap between second and third was too wide. On open twisting lanes the Sprite comes into its own, quick and safe driving requires a decidedly delicate touch. Too heavy a hand at the controls would easily induce the twitchy character of the short wheelbase, and terminal consequences. Above all, the car is immense fun, and my smile matched the happy grin on the grille! The Turner naturally has all the plus points of the Sprite's character, but with a good deal more refinement. The seats have a glass-fibre base and back, but are bolted to the floor pan, unlike the Austin's which are fully adjustable. The instrument range is identical to the Sprite, though a glovebox is included on the dash as is an ammeter, and the steering wheel is three-spoked. When the deep doors are closed, elbow room is very restricted and much more cramped than on the Sprite. You soon develop the tendency to rest your elbow on top of the door. The ratchet handbrake is also a long stretch to the passenger footwell, proving that Jack Turner regarded the overseas market as more important. Fast bends Driving the Turner is reminiscent of guiding a powerful motorcycle through fast bends. The handling is simply superb once you are attuned to its precise characteristics, and the equal weight distribution at front and rear prove the invaluable racing experience of Jack Turner. The Turner's lighter weight, helped by the Alexander tuning mods, gave it a definite edge on performance, with a good deal of extra torque. The Climax powered Sports must have been a revelation back in the early sixties. Both cars have immense charm, and even during my short acquaintance became very addictive. Although the two models have the same basic chemistry, the reality is quite different. The 'Frogeye' was a very basic sports car created for a huge mass-market at modest cost. It could be enjoyed by everyone from swinging fashion chick to frustrated biker, whose girlfriend insisted he buy a car. The Turner is altogether a different breed. It is more an enthusiast's sports car, built for the motorist who appreciates superb chassis design and the potential for competition racing. The basic package provided unlimited tuning possibilities, and thus had a more individual image. Today both have assured classic status, although the rarity value of the Turner and its simple, relatively rust-free design make it more attractive to the DIY restorer. From the styling viewpoint, the 'Frogeye' is now the more distinctive, as Terry Filby will acknowledge: "I had to put the name on the side because everyone kept confusing the Turner for a Midget".

|