| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| The late fifties and early sixties saw a new type of car in Britain - the GT. They were not Grand Tourers in the tradition of Alfa Romeo, DeLahaye or Bugatti, but were small, closed sports cars which paralleled the cars that firms such as DB and Nardi has been making on the Continent for years. Britain was late getting the type, but once the idea had been planted, the species proliferated.

During a short period , roughly from 1957 to 1962, the British buyer went from having nowhere to turn for such a car, to being spoiled for choice. Among those offered were TVR, Grantura, Lotus Elite, Marcos, Arnott, Peregrine, Falcon, Peerless, Heron GT,Reliant Sabre, EB Debonair, Diva GT, Ginetta G-4, Falcon 515, Tornado Tailsman, Deep Sanderson, Rochdale Olympic, Ogle SX-1000, Turner GT and Elva Courier GT, just to name those which immediately spring to mind. Many were, notionally at any rate, dual-purpose cars, to be used on the road during the week and on the track at weekends. There had always been dual-purpose cars, but the new breed reflected the times and catered for the driver who did not want to suffer the elements for 355 days of the year so he could have fun on the remaining ten. As the fifties wore on sports cars had been increasingly sold, in Britain at least, in coup´e or hardtop versions, so the GT was a natural extension of the trend. Better roads and the opening of the M1, then de-restricted, had given a new perspective to high-speed motoring. More than that, many makers discovered what the Germans and French had known for years, that a GT car could have better aerodynamics and greater rigidity than an open car. Broadly speaking, the new breed of GT came from three main strands of the specialist tradition of the time. In the case of Lotus and Elva, a maker of competition cars expanded into a new field and put its reputation and expertise to good use. Some, such as Reliant and Turner, were established makers entering a new market, while yet others came from the special-building and tuning boom of the late fifties. No matter what the background of each company, most were helped by the introduction of a new generation of small capacity ohv Ford engines allied to excellent gearboxes - and the willingness of Ford, then as now, to sell them to the little guy. At the time these cars came out I was a student some distance away from owning my first Ford Pop, let alone a GT car, but one could dream, and it was about those cars I did dream. An E-type or a DB4 would have been good sure, but were so far out of reach as to be sheer fantasy, like dating Brigitte Bardot. A TVR or Turner was more possible , I could relate them directly to my starting salary (if I lived in a tent for two years, and lived on a can of baked beans a day, I could buy one!) so the dream was more intense. Such a car would not only assist in cutting a wide swathe through the local crumpet but could see me on the ladder to becoming World Champion. Time passes and you forget these things, but when C&S asked if I would like to spend a day driving some examples of the GT genre, I leapt at the chance, and the old memories came flooding back. I was prepared to be disappointed, of course, but in the event I had the pleasure of driving three interesting cars, which are still fairly inexpensive to buy, but which could serve as sole transport during the week and be used for the odd sprint or handicap at weekends. As luck would have it, when we found three specimen cars they each represented one of the tributaries from which emerged the flood of sixties GT cars: an Elva Courier GT, a Turner GT and a Tornado Talisman.

Elva was a maker of sport-racing cars founded by Frank Nichols, who was essentially a businessman who employed a succession of designers. His first production sports car, introduced in 1955, found a niche somewhere between the Lotus 6 and Lotus IX. In Britain it was seen as a competent clubman's car, the serious racer went to Cooper or Lotus, but one of the improved Mk II versions was bought by Chuck Dietrich who had a very successful time with it in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) racing, particularly in the mid-West. SCCA racing was strictly amateur, so a good driver such Dietrich did not face works teams as he might in Britain, where Lotus put the cream of young drivers under contract. This suited Nichols, who did not want his profit margins eroded by works teams or appearances in prestige events such as LeMans. So while Colin Chapman set himself seemingly impossible tasks and relied on accountant Fred Bushell to find the wherewithal, Nichols happily sold cars to America and counted the dollars. Elvas were good cars, if not quite as good as contemporary Lotuses, but the fact that they were being used in amateur racing with no works cars to set a standard meant the differences between the marques was perceived to be much less in the States than in Britain. While Chapman struggled to get his revolutionary Elite into production (and he lost money on every one sold), Nichols commissioned Peter Knott to design the Courier, a sports car built around a tubular chassis, a glass-fibre body and MGA components. It broke no new ground but was successful in its class at club racing level, and it made money. Although Elva came on to the market after Lotus, by 1960 it was almost certainly making more cars each year. Everything was going swimmingly until the American importer was hiked off to the hoosegow for financial irregularities and Elva went under. The Courier project was sold to Trojan while the racing side reformed and continued successfully for some years until absorbed by Trojan to become the manufacturer of McLaren Can-Am cars. Jack Turner was an engineer who began by building a special for his own use and found himself pressed to make replicas. His first cars were similar to contemporary Coopers and Tojeiros, in that they were a ladder frame with transverse leaf suspension to which a customer would fit his own body and running gear. Turner made eight of these, one of which was used as the basis for an F2 car for his friend John Webb (not that John Webb). This car, which has an alloy-block, fuel-injected Lea-Francis engine did not exactly take the world by storm, and neither did an air-cooled four-cylinder dohc 500cc engine intended for F3. Realising that he was not going to establish himself in racing, Turner decided instead to build a small sports car using a ladder chassis, glass-fibre body, and BMC A-Series components, and this appeared three years before the Sprite. Since BMC had the 'Frogeye' under development, it is not surprising that Turner had to buy all his parts through his local BMC agent, which added to the cost. Still, the little car won a lot of friends, and races, and was made at the rate of almost three a fortnight for ten years, with later models more often than not using Climax and Ford engines. Turner was aware of the danger of being a one-product maker and so planned a second string to his bow - the GT. This had a sheet-metal monocoque to which a glass-fibre body was bonded and it made its debut at the 1962 Racing Car Show where it had a 1340cc Ford Consul Classic engine. Because the GT was intended as a full-back model and the sports car was still selling well, Turner did not promote it (this article is the nearest there has been to a magazine road-test of it) and, consequently, only nine were made. At the beginning of 1966 Jack had to undergo a lengthy spell in hospital. At the time sales were beginning to falter, but his health meant he could not respond. He knew that if his company was to have a future it would have to be restructured, but with his own future uncertain, he decided to close down. He eventually recovered and is currently enjoying his retirement in South Wales. In the late fifties there suddenly grew up a minor industry dedicated to converting old Fords into sports cars. A Ford Eight or Ten could be bought for a few pounds, the 1172cc Formula was burgeoning, and the acceptance of glass-fibre meant that almost anyone could market a shell.

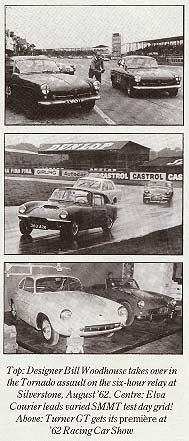

Buckler, Lotus and others had long sold kit cars, but they were in a different class and beyond the means of many people fired with the dream of building a special. A lot were carried away by the notion that all you needed to do was buy a Ford for £20, a body for £60, and the rest was simply a tool kit and dedication. For some people the idea that a body-mounting frame might be a good thing was something which had not crossed their minds, for the most prominent price in the ads tended to be that of the bare shell with details such as the fact that the doors were uncut being down in the small print. One who discovered the snags the hard way was Bill Woodhouse, an ex-RN officer with an engineering background. After building a couple of specials and discovering all the pitfalls, he combined with a friend, Tony Bullen, and set about designing a thoroughly practical kit which the average home constructor really could put together; this emerged in late 1957 as the Tornado Typhoon. Bill was not the only person to have the idea, for the Walklett brothers just beat him into the market with their first Ginetta, the G2, which followed the lines of the Lotus 6. The Typhoon was an ugly car, and Bill accepts that, pointing out that it was designed to accept a range of engines, and in 1172cc form, with 17in wheels, it was over-bodied. It was, however, properly-engineered and extremely good value. For just £70 you could buy a tubular frame complete with a split-axle ifs conversion for which most firms charged around £35. The body, at £130, appeared more expensive than most on the market but it was well-made and complete. Since there were no hidden extras the shell was probably the best value available. Tornado claimed it was possible for the ordinary buyer to build a Ford Eight Typhoon for £250 and when this was doubted, Bill produced the receipts to prove he had done it. Tornado's history is fascinating but is for another time. Suffice to say that around 350 kits of the Typhoon series (including the 105E-engined Tempest) were sold over five years and these included some two-plus-two lwb cars, and even a sporting estate version. More to the point, most kits sold were actually completed, and that is a boost which some kit car makers of today cannot make. In 1961 Tornado introduced the Talisman, a four-seater GT car of striking lines which came with a Cosworth-developed 1340cc Classic engine, though a 'Touring' version with a standard engine was also available. These won immediate approval and were soon being made at the rate of about five a fortnight (189 were made in all) and it must be emphasised that the Talisman was either a factory-built car which cost around £1300 or else was sold in component form to escape purchase tax, in exactly the same way that the majority of Lotuses were sold. Bill says: "It was the nearest thing to the 1300cc Alfa Romeo Giubetta, except it out-performed the Alfa. Unfortunately, our extra 40cc meant we did not compete in the same class." The partners in Tornado Cars were enthusiasts and were content so long as they could make a living and have some racing. Bill again: "We should have re-invested but we were actually ashamed of the idea of making a profit." Eventually, he realised that the company's future depended on an injection of capital and increased production. Colin Chapman was interested in taking over the project but than had a sticky patch. Tornado went into voluntary liquidation in 1963, a case of acknowledging that it was better to go then than suffer later, almost inevitable, collapse. The company was bought by John Backart, a noted amateur racer, who thought the way to go was to cut back production and extend the tuning side of the business. He attempted to market a Fiat 600 with a Ford 1500 GT engine, but only three were sold. Within a year Tornado was history.  That, then, is a brief background to the three makes. On a misty day in late October we assembled at Chobham to drive and assess the cars. Of around 600 Elva Couriers made, only 33 were coupes, most of which were really only permanent hardtops with a reverse rear window recalling the 105E Anglia. The Courier GT proper was a fastback, but few were sold, for the tiny rear window was not liked, and nor was the fact that the Courier's excellent luggage capacity vanished with the new roofline and the boot became a repository for the spare wheel and not much else. Peter Jackson has owned his Courier GT since 1972. "I was looking for an Elan when I saw it advertised for £265. The chap selling it said it was the ugliest car there was but it took my fancy. He also said it was the prototype coup´e and the 1962 Motor Show car, but that's what everyone says! It certainly has an original Elva round-tube chassis and not the later Trojan, square-tube frame." Prototype or not, Peter's Mk III is still a rare Courier. When Trojan acquired the project it took over the existing round-tube chassis and the first 25 cars were built on them. Later came three coup´es using the same style of frame but fitted with irs, and it is likely that Peter owns one of these. It has the 1622cc 78hp MGA engine and the bonnet scoop which appeared on some, but not all, Mk III's. "Cooling is critical," says Peter. "On a hot day the removal of the radiator grille can make a difference of between five and ten degrees." Having bought his car as a runner in need of attention, Peter set to work to make it into practical road transport which still does about 3000 miles a year, with a Minor 1000 Traveller being used to carry loads in conjunction with his job as a motor engineer. The frame needed derusting and he also modified the rear bodywork, fitting an MGB GT heated rear window, a rear wiper, and a neat lip to the tail which is an improvement on the original. When you climb into the cockpit - which is not in one fluid motion, for the doors do not open wide and Peter has had high-sided seats fitted - you feel you need a conversion course for there are instruments everywhere and a large panel of switches in the roof. "I was working for Bristow Helicopters at the time and I think I envied the pilots their cockpits." Forget choppers, we're talking Space Shuttle. To generate the wattage to drive such as electric windows an alternator has replaced the dynamo. Some may raise their hands in horror at the modifications but I feel it's an honest example of period customising and, while not to my taste, all the alterations at least have a unity of style. The pedals are off-set to the right and it's best not to wear too broad to shoe - you can so easily hit two pedals at ones. A small steering wheel has also been added, which is fine from the point of view of steering, but it does obscure the speedo. The first impressions communicated when driving the car (and it is a car which does communicate with the driver) are how good the ride and the steering are. Handling is of a high order by any standards and the roadholding is neutral. On Chobham's sweeping curves the Elva could be placed precisely by minute adjustments to the throttle. It's the sort of car which makes any driver feel good so it's no wonder they were popular, and successful, in club racing on both sides of the Atlantic. This particular car was raced in the sixties by a Dr. Longton and at one time Peter considered fitting a Ford V6 engine to it. The chassis certainly feels as though it could accommodate the extra power and in this case is helped by having slightly winder-than-original tyres. When the Turner GT was first shown at the 1962 Racing Car Show, it did not receive a great deal of attention, for in those heady days the Show was an occasion for major launches and it was swamped by among other exhibits, the new Lotus 22 and 23, and Elva's Mk 6. On its stand, however, the Turner looked magnificent and one thought at the time that it must become a strong seller. Petula Clark was a notable owner of a yellow example. For reasons already given, that was not the case, but Turner's decision not to promote the car for the time being is only part of the story. Seeing one again after a quarter of a century it's easier to see why it did not sell. From some angles the Turner is stunning but from others it looks odd, as the delicate roofline disappears and the rear wings take on the appearance of large slabs. When new, as a fully assembled car, it cost within a few pounds of the Tornado Talisman (and the MGB) but while the Talisman came with a Cosworth engine, the Turner had only the standard 1500cc GT unit, and in contrast to the Talisman's clever use of interior space, which made it a full four-seater, the Turner's claim to be a two-plus-two is dependent on the '-plus-two' section being occupied by a couple of bonzai toddlers. The boot, also, is too small. A potential buyer would not have been encouraged by the fact that there were no published road tests to give a guide to performance or road behaviour, and neither were the cars raced. While the Turner sports car was continually improved in all areas, the GTs which were sold were basically replicas of an imperfect prototype. Twenty-five years on, one sees it in a different light. Only four of the original nine are known to exist in the British Isles and the example (No. 8) owned by Barry Smith is one of two known runners. It is, therefore, an interesting, if flawed, rarity which has the cachet of a solid family name. Barry, who is a glass fibre prototype maker, also owns and races a Turner Mk 1. "I bought the Mk 1 in 1975 and two years later I was looking around for a road car, preferably another Turner, when this came up. It was in a bit of a state when I bought it but I restored it." One might add he restored it to the standard one would expect, given his occupation. "It can be a pain to maintain, the windscreen is a special Turner job and while the front suspension is simple enough, being Triumph Herald, the rear end is pure Turner with trailing arms, coil springs and Panhard rod, different from the sports car which has torsion bars. Still, it handles well, drives well - and leaks like a sieve." On the circuit, Barry's claims for the handling were borne out. In fact it was a very placid drive, for no matter how hard one tried to catch the car out, it coped. Lift off in the middle of a corner and nothing happens, the car sticks to its line. You have the impression that the monocoque is very stiff indeed and cries out for more power. While the utilisation of interior space is poor, the instruments are particularly well-arranged. The Turner GT is so very nearly an excellent car. The basic concept is right, and the chassis could find acceptance today, but the body would need re-thinking inside and out. For a company which built so ugly a beast as the Typhoon, the Talisman was a surprise, but Tornado had the prototype built by Williams and Pritchard in aluminium to a design by Colin Nextall and modified it until is passed muster. Then it was reproduced in glass-fibre and bonded to a very strong ladder frame with all-independent suspension by unequal wishbones. From almost any angle, the Talisman is a handsome car and the interior is particularly well conceived, being a genuine four-seater with adequate luggage space and a pleasant dashboard. "A few years ago it took my wife, myself, and our son, then 18 months old, on a month's camping holiday to France," says Dudley Guest. Tornado's engines were built by Cosworth, and Keith Duckworth himself selected the blocks. The A2 camshaft is similar to that used in the 1500 GT but was made by Cosworth to its original design without the compromises which had to be made when Ford put it in production. When the engine was delivered ( at £45 a time) Tornado fitted two twin-choke 40DCOE2 Webers and a special exhaust manifold. In 1340cc form, these engines produced about 75bhp, with excellent mid-range torque, while some later cars were fitted with a 1500cc version which had 86bhp on tap.  With either engine a Talisman would cruise at 90mph, and top the ton, so while it might be a surprise to learn that they were eligible for saloon car racing, it should be less of one to know that they were successful when they did race. Contemporary reports treated the Talisman with respect and one gathers it was thought to be one of the best-handling four-seaters on the market in 1962. Dudley's example is fitted with a full roll cage because he undertook a season's racing in 1982 and, in fact, upheld Team Turner's honour in the Silverstone Six-Hour Relay race when for nearly two hours his was the only operational car. There is some justice in this, for in 1962 a team of three Talismans won the event outright.  All three cars in our sample had glass-fibre bodies of a high standard of build but the interior of the Talisman was particularly pleasant. The overwhelming sensation once underway is that the Talisman is undergeared and Bill Woodhouse is the first to admit that it could have done with a higher rear axle. For most purposes, then first gear is redundant and in practice one would rarely have to drop below third on the road. Its steering is the lightest and most sensitive of the three, a little too light and too sensitive for my taste, and though the roadholding is of a high order, the Talisman is the twitchest of the trio. The Tornado, however, keeps no secrets - it always lets the driver know what is happening, and what is likely to happen. It manages to pull off the hard trick of being a true sports car while remaining a practical four-seater. As with the Elva and Turner, the ride is comfortable and while the engine is noisy, most of the decibels come from the four Weber chokes gulping in air, a sound I find pleasant. The noise of honest work from a car's underbonnet has never irritated me. Give the chance to own one of them, I'd find it a difficult choice. The Elva has the most sporting feel, as you would expect from a maker of racing cars. From some angles the Turner is the prettiest, and it is the most rare, but it needs more power to bring out its virtues. The Talisman has the most modern feel and is altogether the more practical but I would certainly want a higher back axle ratio. Of the three, the Talisman engenders the most regret. It should not have been allowed to die and it leaves one with the tantalising prospect of what the Tornado team might have achieved. Each car has a lot going for it and from the point-of-view of the potential purchaser, each is an attractive buy, for spares are readily available and the bodies will not rot. Further, as interesting cars attract increasingly silly prices, each represents a chance to buy an unusual, and competent, car at a reasonable price. I do not think any of them should be viewed as a blue-chip investment, but each is a good all-rounder which could be used as sole-workaday transport with the possibility of taking in a few grass-roots competition events. Each too, is an interesting design representative of an era when, almost overnight, British makers latched on to the idea of GT cars and offered buyers a bewildering choice.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||