| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

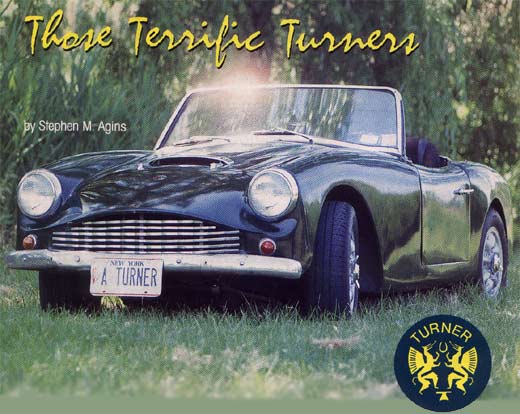

| It's worthy of a movie treatment: The big war is over. Aircraft engineer has a brainstorm for a basic entry-level sportscar. He buys components at wholesale prices from a half-dozen major manufacturers, adds touches of his own technical genius; starts assembling and selling cars in a blacksmith shop and pretty soon owners are out on the race track beating the pants off the 'establishment' sportscar of the day . . . Petula Clark, a famous pop-singer/actress buys one adding to the glamour. Almost singlehandedly, he had developed a niche in the sportscar market. Then . . . enter the 'heavy'. Giant manufacturer smells profits in the labors of the engineer; secretly authorizes design of its own version of the new car and then when it's ready for introduction, cuts off his customer/competitor's wholesale supply of vital parts. Fledgling company struggles on for several years eventually succumbing to a combination of problems including a mysterious US destributor who absconds with a half-dozen cars. If Hollywood producted this, of course they'd film plenty of crash-and-burn scenes; a couple of exotic chassis, one a blond and the other a brunette; races in which - no doubt - Hollywood would hve Super Vees and Chrysler 300's on the same track with our hero's Austin-powered component car; maybe Al Pacino, you know . . . the whole nine yards. But we're not writing fiction. Welshman Jack Turner built and ungainly-looking little car using bits and pieces from a number of different manufacturers into a total of 670 two-seat sportcars that were both swift and surefooted, between '53 and '65. Today, about 300 - roughly 45 percent - survive. Here's an automotive enigma if there ever was one. Turner felt the Triumphs, Austin-Healeys and even the MGs of the early 1950's were too fancy. He decided that the market needed something else. "Just a simple car a young man could afford is how he described his first models 803, 950, Mark I, II and II Turners. You have to understand, Jack Turner's idea of a simple, basic, no-frills car is one where the heater was an extra cost option. Turner was one of several entrepreneurs who fathered a genre of cars built with batches of engines, suspensions, steering gear, drive trains, windshields, doors, hinges and handles, and bits and pieces of hardware from the major manufacturers. The marques born in the Heinz 57 theory of carbuilding: Lotus, Elva, TVR, Turner and other have left more lasting memories than prom night at the beach. Essentially, all of the Turner sports cars were built on a parallel tube chassis initially using the Austin A-40 front suspension, steering, 30-horsepower engine and gearbox. Jack Turner had designed a unique rear suspension which incorporated transverse torsion bars with trailing arms to the rear axle assembly, tubular shocks, and a panhard rod. This rear suspension worked so well that Turner incorporated it into three later generations of production sportscars that he built between March 1955 and April 1966. To this day, the drivers campaigning Turners in SCCA national races, against much more sophisticated and well-developed racers, believe that Jack's suspension if one of the key reasons for their success.

He produced what he believes to have been the first mass-produced fiberglass automobile body for his cars, starting in 1953 with the Model 803. While nearly all of the bodies were fiberglass roadsters, six steel-bodies cars were produced and two are known to be in the US. Also, 10 GT bodies were produced in fiberglass and at least one is in the United States. Turner's work force ranged from six to twenty-five, and began operations from a blacksmith shop known as The Smithy. They produced about 100 of the 803s and then as the Austin engine was upgraded, body refinements and design elements were incorporated into the 950 (a whopping 170 of these were produced) and then the MK I Turner (160), the Mk II (150) and the Mk III (80) were manufactured. The basic engine/gearbox combination for this car is the same unit found in many different states of tune and in many different cars such as the Morris Minor, and the Sprite. And there's the catch, the car we know as the Austin-Healey Bugeye Sprite here, and the Frogeye, over there. During 1955 to 1959, as Turner was building the models 803 and 950, he believes that Austin's Managing Director, George Harriman, had started to covet the niche that Turner was carving, both as a race car and as a product that could introduce first-time sports car buyers to the joy of performance motoring. According to Turner, George Harriman commissioned Donald Healey, who had been doing Austin's development work, to build their own entry level car. Jack Turner charitably commented on the result, "I've no doubt that Healey had a good look at ours one way or another. I find it curious that their car should come out on very similar specifications to ours," he said from his retirement in Crickhowell, Wales. And similar they were. Both cars shared Austin components on a simple chassis (the Sprite used a platform), both were sparten and both were a bit odd-looking. While the Sprite weighs about the same as the Turner, the parallel tube frame brings Turner's weight down low close to the road, compared with the Sprite's steel body which places the weight higher. The very low center of gravity was another plus in the Turner's cornering ability. Styling features of the 803s and 950s included a too-large eggcrate style grill, wheel arches that were visually too large for the original-issue tires, and doors hinged on the trailing edge. The 950 is identified by little fins atop the rear taillight housings. The added power and braking ability combined with Turner's rear suspension to make the 950 into an extremely successful club racer. In fact, Turner 950s won the UK's Autosport Team Championships for production cars (roughly similar similar to the SCCA) outright, in both 1958 and 1959. There has been some despute among various vintage race sanctioning organizations in recent years about the original size wheels with which Turners were manufactured. Jack is very specific: "I offered my Turner sports cars with 13-inch wheels in every year until 1965." The Hollywood script writers wouldn't have to invent the next part. Austin's George Harriman cut Turner off from wholesale priced supplies of engines, steering mechanisms, brakes and gearboxes from the factory. As a result, the relatively streamlined, and therefore commercially viable, Mark I Turner came onto the market in late 1959 at about £575, £100 more expensive that intended. And coincidentally, perhaps 30 percent more expensive than the early Bugeye Sprites. With his major supplier suddently a competitor for the very market niche he had defined, Turner made a wise decision to diversify, offering several different choices in running gear and power. The Mark II made its debut in 1960. Its mechanicals utilized the Triumph Herald front suspension which included larger disc brakes, and basic Sprite engine. A wide grill opening using a specially-pressed Mini-Cooper look-alike grill, and a more graceful rear section gave the car an attractive appearance that hardly looks dated today. There was a real departure under the hood. By this time (1960), you could buy a Mark II with a 1340cc Cortina (non-crossflow pushrod) engine. The 1500cc Cortina engine, which became available in 1961 in its most conservative form, could put 80 ponies to work. It transformed the 1,300-pound MK II and MK III Turner into very formidable street or racing machines. Throw a few thousand dollars at this engine today and it's easy to get 120 bhp on pump gasoline. The cross-flow Cortina engine, found in Pintos, and used in Formula Ford racers, is a bolt-in installation which isn't a legal proudction option for any US racing or autocross, but it is an inexpensive and readily available replacement for the now-scarce non-cross-flow cylinder head. By the end of 1964, the standard setup for the Mark III was the 1500cc Ford Cortina engine, larger discs and 8-inch drums in the rear. Ford's 997cc and 1,340cc pushrod fours and two different Coventry Climax engines were also available for special purchase. The sad end of the company came in 1965 when an American dealer in California took delivery of six cars and managed to avoid paying Turner for them. Ultimately they were sold at a radically reduced price. Race driver Larry Moulton believes that some of these cars may have been in a Utah showroom that year. But they seem to have disappeared when the dealership failed and the owner apparently left town in a hurry. Sidelined temporarily with health problems, Turner was unable to muster the energy and resources needed to pursue his missing cars and the designand manufacture of a new line. But the name lives beyond its 670-car production run. Turners have a cult of followers in many countries, and they keep in touch through a newsletter. Also, the body shells, windshields and certain suspension pieces have been re-manufactured in England and are available through the Turner Register. At various times Turner shipped cars to India, Australia, South Africa, West Germany, Holland and France. Approximately 25 percent of early Turner production run was exported. Of the last 145 cars, some 68 were shipped to the US. There are numerous owner who have had their cars for more than 20 years, and several 30-years-plus owners, some of whom still use them for transportation and frequent competition. Many are being raced in SCCA and various Vintage races in the US today with a great deal of success. In fact, two won their class in Sebring in 1960. Larry Moulton of Sandy, Utah, won the national SCCA F-production chanpionship in 1984, 1986, and 1989, and placed second overall twice and third twice in 11 years. Fred Leib of Nashville, Tennessee, whom contributing editor Burt Levy has written about on these pages, purchased his Turner 950 new in 1958, then entered and completed Sebring in 1959. Before the 24-hour race, Leib's car had never even been on a race track. After the race, he flat-towned the car home and drove it to work the following day. Just this past Autumn, Leib won his class at the Road Atlanta SVRA meeting in the same 33-year-old car.

Barry Prehodka of Ridgefield, Connecticut has captured more than 25 firsts in class and approximately 15 outright race wins in VSCCA, VRAC and other vintage races driving one of the 1960 Sebring cars, a Sprite-powered MK I. For a car that was built as a sportscar, not a racer, with no R&D department, no sponsorship, no dedicated aftermarket manufacturers, no high-tech engineering assistance and in fact no factory, Turner sportscars continue to enjoy admirable success in competition, and a firm hold on the hearts of the owners. For information on membership in the Turner Register write to David Scott, 21 Ellsworth Road, High Wycombe, Bucks, HP11 2TU England. In the United States, contact the author at 135 West 94 Street, New York, NY 10025. Note: The current (Nov 2000) address for Stephen Agins is: 1530 Palisade Avenue #11S Fort Lee, New Jersey 07024 Telephone 201-944-4037 Facsimile 201-944-0692 |