| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

How embarrassing. I had spun the Turner, depositing in the dirt in a shower of mud and dust. Naturally enough, I had stopped spinning facing the track so that I had to witness the procession of seemingly everyone out on the track. All of whom had been not far behind me when I spun. And all of whom, of course, would be sniggering in their helmets about the contretemps of the hot shot journalist. I kept my eyes fixed on the corner workers so I wouldn't have to look.

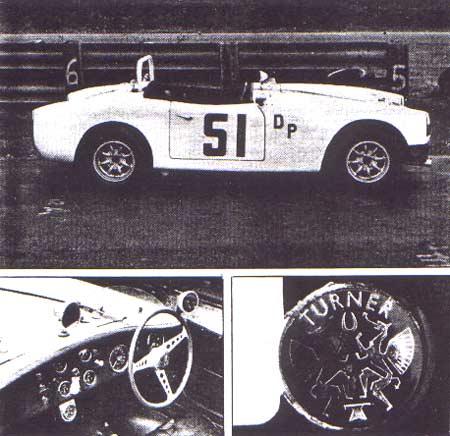

How embarrassing. I had spun the Turner, depositing in the dirt in a shower of mud and dust. Naturally enough, I had stopped spinning facing the track so that I had to witness the procession of seemingly everyone out on the track. All of whom had been not far behind me when I spun. And all of whom, of course, would be sniggering in their helmets about the contretemps of the hot shot journalist. I kept my eyes fixed on the corner workers so I wouldn't have to look.I had pirouetted no ordinary Turner into the tulies. Rather this was the '65 Turner 1500 MKIII in which Ron Kistler had won Nationals at Marlboro, Vineland, and Cumberland in 1966. Winning three Nationals is not in itself so remarkable - though no mean feat - but that the car has escaped the normal evolutionary changes a race car endures as it passes from season to season is rather unusual. The Turner, now in the hands of second owner Allan Modney, is all original, even down to the scrapes where Kistler squoze Dick Thompson's Yenko Stinger off the track at Cumberland. Original even down to the bungie cord Kistler had applied to the trunk lid to make sure it stayed closed in the heat of battle. That's original. Kistler had ordered the car from the factory for SCCA D-production racing - right-hand-drive, Cosworth motor and no heater. Windshield and top were sent along in a box. The Ford pushrod engine, dominated by twin 40 DCOE Webers, was dynoed at 135bhp. Koni shocks were installed in front with revalved Armstrongs at the rear. A front sway bar was added and the front shock towers reinforced. Other modifications included cold air ducting to the carbs, oil cooler and brakes, a Lotus close-ratio gearbox, Detroit Locker limited slip and Hollywood competition axleshafts. Weight is 1,250 pounds, less that 10 pounds per horsepower.  Though he had been SCCA's Northeast Division C-production champ in 1963 in an AC Bristol, Kistler was forced out by finances halfway through the 1966 season. A rule change for 1967 outlawed the twin 40 Webers, and the allowable two-barrel downdraft Weber left the car uncompetitive. Kistler parked it rather than race at the back of the pack. It stayed parked until 1981, when Kistler sold it to Allan Modney. The car's only outings since then have been the 1982 Walter Mitty Challenge at Road Atlanta and my, uh, spin at Summit Point in the fall of 1982. The car has less than a thousand honest miles on its odometer. The Turner MkIII was both the high point and the end of the line for J.H. Turner's car company. It had begun in what was a classic pattern in Great Britian in the '50s and '60s. Turner's racing success in an MG K3 and a homebuilt Formula II car led to a handful of replicas of the latter. Then, in 1955, came the little Austin-powered Turner 803. Over the years his sportsters, based on a rigid twin-tube ladder frame with suspension bits from various sources, grew in power and sophistication. Bigger Austin and then Coventry Climax engines were used and then Ford, the largest being the 1,500cc Cortina unit, producing 80bhp in street trim. The use of a variey of suspension pieces resulted in some cars having different bolt patterns front and rear.  Turner utilized fibergalss for bodies, bonding it to the frame. None were of particularly exciting shape, perhaps best described as inoffensive. It takes a practiced eye to pick one out in a crowd. Modney, who has owned 10 Turners at one time or another, says that details often changed from one serial number to the next, especially with small parts like taillights. It's almost as if the shop gopher were sent with a fistful of sterling to buy a case of whatever rear lamps were on sale - anonymous styling if ever it existed. Which probably suited Jack Turner, for if a "sports car" is a road car which can be raced, then what Jack Turner produced were race cars which could also be driven on the road. And you don't win races with pretty faces. If the exterior styling is unremarkable, the interior is commonplace. The dash, with its off-the-shelf gauges, is straightforward. The driving position is terribly normal feeling despite the right-hand-drive. Even the absence of a full windshield in favor of a small racing screen seems natural. The car somehow belongs this way.  With engine warm, starting is easy. The big Webers, though, don't take well to idling, the engine refusing to hold a steady speed even with a little extra RPM. Blipping the throttle is a necessity. All is forgiven coming out of the pits, though. The English Ford buzzes like a band saw on piece work and I get an authoritative little shove back into the seat. The stubby shifter clicks precisely into second, zig-zags to third and back to fourth. Before I know it I'm up against the rev limiter in high - somewhere just to the far side of 100 with this rear end. The car is quick. Also quick and very sensitive is the steering, and my path for about the first lap resembles that of a novice canoeist. Which is to say where the track went straight, I didn't. Once I got that under control, another problem arose - the cold surface of the track. Late November temperatures didn't allow the racing tires to get anywhere near warm, the result being a very skatey ride in the corners. Still, after a few laps and self-admonishment to practice driving-school smoothness and journalistic restraint - this is, after all, for a driving impression, not setting a lap record - it starts to come together for me. Steering sensitivity becomes responsiveness, and I'm able to match the overabundance of power with the limited traction available. I'm starting to draw a bead on the other traffic on the track. Not racing, mind you, but close enough. Then, closing on Max Rubin's BMW 323I, it happened. The Turner went off song, missing on one or two cylinders. Instead of swinging past the Bimmer, I swung into the pits. The trouble, we eventually discovered but couldn't immediately remedy, was fuel blockage to one of the carbs. Racing luck. Like spinning out. My excuse (everybody has one) was getting on the gas too soon and too heavy on those cold, hard tires. In a way, it's a bit like what brought about the end of Jack Turner's car building. Turner had tried to do too much, producing a GT model introduced in 1962, and of which only nine were made between then and 1964. Another fixed-head model with a rear-mounted Hillman Imp engine reached prototype stage in 1965. These two projects, plus an effort to develop a twin-cam head for the BMC "A" block, lost a lot of money. Over the years, Turner had built about 750 cars, cars that achieved racing successes far in excess of their production, but in 1966, Jack Turner spun into receivership for trying too hard. |