| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

|

| A smooth finish is achieved on the glass-fibre body. With the latest modifications, the rear wing lines slope down to join the rear light clusters. | |

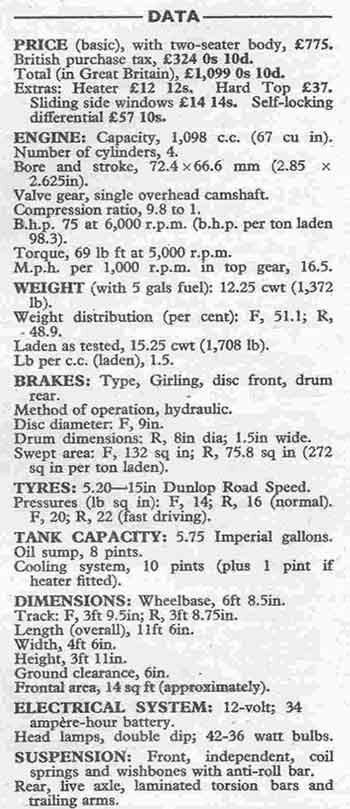

| BUILT in small numbers in a factory near Wolverhampton, the Turner Sports car has the engine size and performance to enable an owner to compete in sporting events with a good chance of success. In the last two seasons, private owners racing on club circuits have succeeded in winning the Autosport Series Production Sports car championship, in cars fitted with B.M.C. A series 948 c.c. engines. Now a version is being produced which is powered by the Conventry Climax FWA 1.098 c.c. unit. The greatest proportion of the factory's output is going to customers in North America and South Africa, and thus the test car was offered with left-hand drive. Like the majority of true sports cars, the Turner has a separate chassis frame, consisting of two main tubular side members joined by cross tubes at the front and rear. Other longitudinal members, pierced for lightness, are supported by extensions of the cross members, and are used to carry the sheet steel body sub-frame and the moulded glass-fibre body shell. The car weighs a little over 12 cwt.

Cars which are built mainly for competition and fast touring cannot be expected to offer the amenities of saloons or open tourers. Basically the Turner is rigid and well built for the work it is intended to do, although on the test car certain shortcomings of detail design were criticized. The manner in which the car performs, and the way in which it enables a driver to blow away the cobwebs gathered as a result of many miles driving in softly sprung saloons, to give a new zest to motoring. The race-bred Coventry Climax engine has a dual personality which is perhaps not well known to spectators at race meetings who usually have heard these power units only in full cry. During the road test the car on occasions was left out in the open, mostly in rain, yet on a few turns of the starter motor (no handle is provided) the engine fired without the use of the choke control. It pulled strongly from cold, though it was not helped by the weather or the wide air intake to the radiator. (It did not normally run hot enough, for the temperature gauge seldom reached 65 deg. C.)

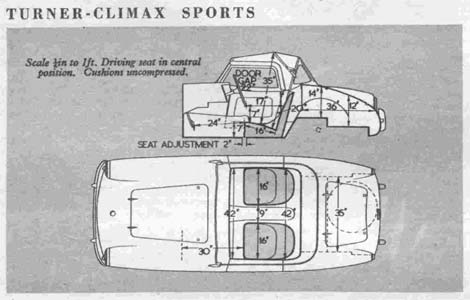

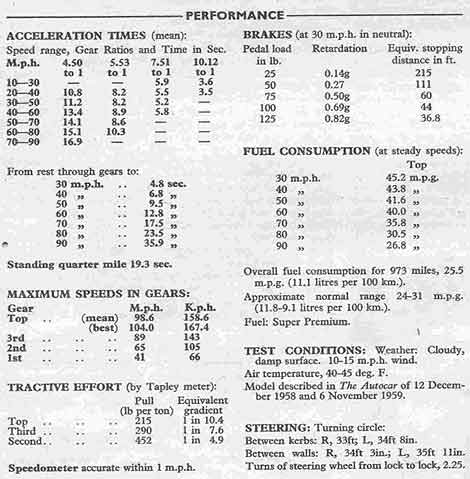

Complementing this easy starting is the way in which the engine will pull quietly and smoothly at around 1,500 r.p.m. in top gear, enabling the driver to enjoy docile progress in built-up areas. It is, in fact, a tractable little car of its type; there is no engine roughness except at very low r.p.m. and it will tick over quite evenly when the car is held up at traffic lights or in rush-hour traffic. A combination of favourable power-to-weight ratio and high gearing produces a moderate petrol consumption figure, for fast driving, of about 27 m.p.g. Oil consumption, on the other hand, seemed excessively high, even for a new competition type engine, five pints being added in less than 500 miles; this may be attributable to the fact that the car had less than 20 miles "on the clock" when delivered for test. Such a consumption is not typical of the Climax 1,100 c.c. engine (which is bench run before installation). Once away from 30 m.p.h. limits, the car became dynamically alive. As the engine speed built up, with the tachometer needle racing round the dial, a crescendo of sound developed which was too obtrusive for British roads - the slight valve gear noise when cold, resulting from one noisy tappet, and the intake roar from the twin 1.5 in S.U. carburettors (no air cleaners or flame traps are fitted), became lost in the chorus of noise in which the strident exhaust was most prominent. The limit of 7,000 r.p.m. was adhered to during the test. With 65 m.p.h. available in second gear and almost 90 in third, the performance can be a new experience for youthful drivers, and a shot in the arm for those who have forgotten what fun can be had with a small car like this. Because of the torque characteristics of the engine, the better acceleration times come with higher speeds; nothing startling happens until the engine speed reaches 3,500 r.p.m., but the little unit really begins to work for its living. A standing quarter-mile figure of 19.3 sec is good without being exceptional (the MGA 1600 recorded the same figure); on the other hand, the 40-60 m.p.h. figure of 5.8 sec. in second and the 60-80 of 10.3 sec in third are both above average in the class. It is a true 100 m.p.h. car, even though, in the somewhat adverse weather conditions of the test and when scarcely run in, the mean achieved was only 98.6 m.p.h. Restarting tests on a gradient were perhaps trying for the high bottom gear of 10.1 to 1, and it was not surprising that the little car only just managed a restart on the one-in-four test slope - helped by some judicious clutch slip. In view of the comparatively high compression ratin - 9.8 to 1 - super premium petrol was used during the test. There are disadvantages in having the tank filler within the luggage locker, not the least of which is the possibility of having personal luggage smelling of petrol; the tank has a capacity of only 5¾ gallons. A B.M.C. A series gear box with special, well chosen close-ratio gears is used on the Turner, and there is a choice of five different rear axle ratios - a standard 4.5 to 1 axle was fitted for test. There was hardly any wheel spin during standing-start acceleration rests, and no axle hop. The gear changer, by a short rigid central lever, is a pleasing one; there is a short precise movement, the gear positions are found easily, and the top of the lever is comfortably close to the steering wheel, though it might be angled forward an inch with advantage to some drivers. First gear has a pronounced whine, accentuated when the hood is erected. A driver unaccustomed to competition cars found difficulity at first in making smooth starts - the clutch requires a fairly heavy pressure to release it, and it is of the 'in' or 'out' variety. The friction linings are bonded and riveted to the pressure plate to stand the strain of competition work. There was no sign of slip during the testing. Front brakes with 9in discs and rear brakes with 8in drums are fitted to this model Turner; they require more than average pressure to secure minimum stopping distances from speed - a pedal effort on 100lb to achieve an 0.69g stop is too heavy. The pedal travel is rather long and insensitive, and the stopping power is not as good as it should be. The brake pedal is awkward to operate, because it is too close to the accelerator, and the angle of attack is wrong. The driver cannot place his right foot squarely on the pedal; only those with small feet and narrow shoes would escape difficulty in the use of the flimsy cluster of pedals. The handbrake is effective, holding the car on a 1 in 3 gradient, but the lever is difficult to grab quickly. Road holding and stability are very good. The ride is firm, as might be expected, and over a second-class road even small irregularties in the surface are noticed. This is a small price to pay for the excellent cornering abilities of the chassis, and there is no roll or tyre squeal, however vigorously the car is driven. It was quite steady at maximum speed, although a strong side wind caused monentary but small deflection when the car was traveling above 90 m.p.h. with the driver only on board. The rack-and-pinion steering gear is very direct, and as there are only two-and-a-quarter turns of the wheel from lock to lock, a slight movement only is necessary on most corners. In fact, driving the Turner is slightly reminiscent of guiding a potent motorcycle through a series of fast bends, the driver not being conscious of turning the steering wheel. The steering has a neutral feel to it, it is a little stiff and there is no castor action. On wet roads the back end of the car will break away quite readily, before the front, if a slide is provoked. A turning circle of 34-36ft is rather large. The weight distribution front to rear is very nearly equal. Seat adjustment is limited to three positions, altered by means of bolts in the floor (to give a rigid mounting), and a tall driver with long legs cannot really get comfortable. In the rearmost position the bodywork prevents any further movement. The seat cushions are small but not uncomfortable, and the backrests are well shaped to steady the occupant when cornering. Though there is insufficient room to adopt a straight-arm driving position, the steering wheel is pleasantly thin and is set conveniently both as to angle and distance from pedals.

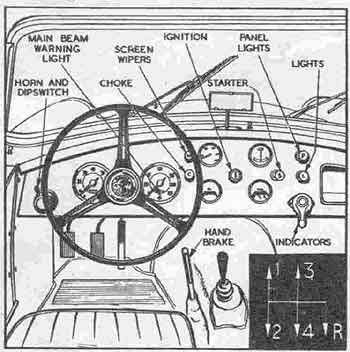

A full range of instruments is provided, well sited on the facia. The tachometer reads up to 8,000 r.p.m., and the matching speedometer is just about accurate. At night the panel lighting does not reflect in the screen; strangely enough, there is no illumination for the water temperature gauge and ammeter. The dipswitch and the button for the single Windtone horn form one unit, on the facia, which can be reached without removing a hand entirely from the steering wheel. The scuttle is low and the action deep enough to permit an adequate spread of vision; the coaming over the instrument panel is sponge-padded. The head lamps have a good range, and in favourable circumstances give sufficient illumination for speeds up to 80 m.p.h. Self-parking screen wipers are provided; they work well at speed, but the blades did not park flat. The direction indicators are operated by a facia-mounted switch which incorporates a prominent warning lamp. They are not self-cancelling. Side-screens are easily fitted, and can be removed or put into position without getting out of the car. In wet weather the windscreen of the closed car mists-up, especially when traveling slowly, and although a heater unit is listed as an extra, no demisting slots are provided in the top of the scuttle; a small flap is formed in the bottom of each side-screen, and if these are left open the misting-up is not so severe. In heavy rain and at speed the side-screens would be more effective if there were some form of clip at the top of each screen pillar, by which they could be secured.

With the hood and side-screens in position, sideways visibility is impaired, especially at the junction of the screens and the windscreen pillars. The screen rail and hood are set well above the level of the seats, giving sufficient headroom, and a tall driver does not have to peer below the windscreen top frame. Somewhat loosely fitted, the hood does not flap unduly at speed, although the sides lift slightly when the car is driven very fast. It is easy to erect, since the hood irons have an ingenious spring-loaded action which is operated when the hood is clipped in position. After the hood is attached, two clips are released and the springs tend to keep the frame pressed up against the fabric. Outside door handles are fitted, with pull wires inside. General finish of the bodywork is quite good, the glass-fibre construction being smooth externally, with good paint-work. A fault developed in the trimming of the driving seat, the material working loose, and the driving side door dropped and became difficult to close. It is understood that later models are to have modified hinges. Under-scuttle wiring, trim material edges and uncropped screw points called for a little more attention. The luggage locker - quite large - is of irregular shape and a part of it is occupied by the spare wheel. When not in use, the hood equipment and tonneau cover must be housed in the locker also. This car, which was built to export specification, had simply carriage locks fitted to the boot lid and bonnet; normally the former has a lock with a Yale-pattern key. No reversing lamp is provided. The tool kit consists of a screw-type jack and wheel nut 'clouter'. The owner of a car like the Turner-Climax might well be expected to be in possession of a collection of hand tools. Greasing calls for attention to ten points, mostly on the front suspension, every 1,000 miles.

Because it is exhilarating to drive, attractive to look at and has a very good performance in its capacity class, the Climax-engined Turner, in spite of its relatively high price, will, like its less-powerful near relation, find approval among enthusiastic drivers.     |